I'm obsessed with creating the world's most awesome web development environment. Part of what I'm aiming for is resident in tributary.io, which I blogged about here. Now another piece in the puzzle that I'm trying to put together is this project: https://github.com/amasad/debugjs.

DebugJS uses a clever hack on the feature called "generators" that's in the new version of Javascript (ES6).

You probably don't care about this, but if you did, here's more than you'd ever want to know about generators, and how to build a VM using them. And here's the payoff: a Bret-Victor-style example using debugjs.

Of course I'm still waiting for Bret to open source the great technology he's used.

Feb 28, 2015

If I did that it would mean...

People often interpret other people's behavior by applying this rule: "If I had done that, it would mean <this thing.> Therefore, <this thing> is what it means."

No, sorry. Sometimes true. Often not.

Example: for years Bobbi would ask me "What are you thinking about?" And it would annoy me. At the same time, it bothered her that I never asked her what she was thinking about. Eventually decoded our behavior: for her, asking what I was thinking was a gesture of interest, caring and respect. For me, it was an intrusion. For me, not asking her was a gesture of respect. For her, it showed lack of caring.

Our kids call up and tell us what's going on in their lives, and rarely ask us what we're doing. Bobbi says it means that they're not interested in us. I say: "That's what it would mean if you did that. They're showing that they care about us by sharing their lives with us. They don't do that with people they don't care about. And when I have something that I want to share with them, I share it. They don't need to ask."

I have a friend who gets annoyed at people who promise to call him and then don't call. "Did they use the word 'promise?'" I ask. "No," he admits, "they didn't use that word. But that does not matter. When I say I'm going to do something it's a commitment. A promise. I take promises seriously and someone breaks their promises it is a sign of disrespect."

That's what it would mean if he did that. What it means for someone else may be the same, or it may be quite different. For most people saying "I'll call you," does not mean "I'll call you."

In fact, it can mean the opposite. The cliche for not wanting to talk to someone is: "Don't call me, I'll call you." So in this case, "I'll call you" means: "I don't want you to call me, and I'm not going to call you, but I reserve the right to change my mind."

"Don't call me, I'll call you" might be rude, but it is more welcoming than "Don't call me. Period." And it's less welcoming than "I'll call you in a week," which might mean "I'm very busy but I won't be busy in a week, and I'll call you in a week;" or it might mean "I've talked to you enough for now. Maybe I'll want to talk more in a week. Probably not before then, so don't bother calling until at least a week has passed."

So when people say "I'll call you," they don't necessarily mean "I'll call you," and they generally don't mean anything close to "I promise to call you."

"I'll call you," is a social convention, and nicely ambiguous, which is one of its virtues. It means something like: "I intend to call you," which means "I have some degree of intention to call you," which may mean "I have enough intention that I am highly likely to pick up the phone and call," or "I have some intention to call you, but my life being what it is, there's a good chance that I will find something that I will find more important," or "I have a miniscule, yet non-zero, amount of intention to call you, and that makes it unlikely that I call, but I don't want to point that out."

Yes, it's ambiguous, but it's a social norm, and most people understand that it could mean any of these things.

Many interactions are coded ambiguously. We don't say things like: "Because I care about you, I'd like to know what you're thinking." And certainly we don't say things like "Because I care about you, I'm not going to ask what you're thinking." WTF? Really?

We assume that people understand the intentions behind our acts, but we're not always right. And that can lead to trouble.

Before being offended because "If I did that, I would be showing disrespect," say: "If I did that, it would mean I was showing disrespect. Is that why you are doing it." You may be surprised at the answer.

No, sorry. Sometimes true. Often not.

Example: for years Bobbi would ask me "What are you thinking about?" And it would annoy me. At the same time, it bothered her that I never asked her what she was thinking about. Eventually decoded our behavior: for her, asking what I was thinking was a gesture of interest, caring and respect. For me, it was an intrusion. For me, not asking her was a gesture of respect. For her, it showed lack of caring.

Our kids call up and tell us what's going on in their lives, and rarely ask us what we're doing. Bobbi says it means that they're not interested in us. I say: "That's what it would mean if you did that. They're showing that they care about us by sharing their lives with us. They don't do that with people they don't care about. And when I have something that I want to share with them, I share it. They don't need to ask."

I have a friend who gets annoyed at people who promise to call him and then don't call. "Did they use the word 'promise?'" I ask. "No," he admits, "they didn't use that word. But that does not matter. When I say I'm going to do something it's a commitment. A promise. I take promises seriously and someone breaks their promises it is a sign of disrespect."

That's what it would mean if he did that. What it means for someone else may be the same, or it may be quite different. For most people saying "I'll call you," does not mean "I'll call you."

In fact, it can mean the opposite. The cliche for not wanting to talk to someone is: "Don't call me, I'll call you." So in this case, "I'll call you" means: "I don't want you to call me, and I'm not going to call you, but I reserve the right to change my mind."

"Don't call me, I'll call you" might be rude, but it is more welcoming than "Don't call me. Period." And it's less welcoming than "I'll call you in a week," which might mean "I'm very busy but I won't be busy in a week, and I'll call you in a week;" or it might mean "I've talked to you enough for now. Maybe I'll want to talk more in a week. Probably not before then, so don't bother calling until at least a week has passed."

So when people say "I'll call you," they don't necessarily mean "I'll call you," and they generally don't mean anything close to "I promise to call you."

"I'll call you," is a social convention, and nicely ambiguous, which is one of its virtues. It means something like: "I intend to call you," which means "I have some degree of intention to call you," which may mean "I have enough intention that I am highly likely to pick up the phone and call," or "I have some intention to call you, but my life being what it is, there's a good chance that I will find something that I will find more important," or "I have a miniscule, yet non-zero, amount of intention to call you, and that makes it unlikely that I call, but I don't want to point that out."

Yes, it's ambiguous, but it's a social norm, and most people understand that it could mean any of these things.

Many interactions are coded ambiguously. We don't say things like: "Because I care about you, I'd like to know what you're thinking." And certainly we don't say things like "Because I care about you, I'm not going to ask what you're thinking." WTF? Really?

We assume that people understand the intentions behind our acts, but we're not always right. And that can lead to trouble.

Before being offended because "If I did that, I would be showing disrespect," say: "If I did that, it would mean I was showing disrespect. Is that why you are doing it." You may be surprised at the answer.

Feb 27, 2015

I Get Lucky (I Love YouTube Search)

Today Mira sent me a song that she's been obsessing over, and I wouldn't be the music-obsessed father and contributor of her music-obsessing gene if I didn't send her back one in turn. Only I couldn't remember the name of the song. What to do?

I knew I'd listened to the song on YouTube, so I started by going through my YouTube history, searching on the word "music" but I've listened to too much music. Or maybe YouTube had started sending me random shit to listen to, because some of the things that came up in history I didn't remember and others I can't even imagine myself listening to. What to do?

After a bit I remembered that the guy who did the cover that I was in love with was named George. George who? George B-something. Well it turns out that that's all you need to tell YouTube. Because I type "George b" and it pops up "george barrett get lucky," which is just what I wanted.

After a bit I remembered that the guy who did the cover that I was in love with was named George. George who? George B-something. Well it turns out that that's all you need to tell YouTube. Because I type "George b" and it pops up "george barrett get lucky," which is just what I wanted.

<3

What George does is sing lead, harmony and backing vocals. Drum set, bass, lead guitar, electronic keyboard, piano, tambourine, cowbell, and a few other percussion instruments, all stuff I'd like to do. And with passion and energy that I don't think that I can duplicate. But jeez, I'd love to.

And now, for those interested, here's the video:

I knew I'd listened to the song on YouTube, so I started by going through my YouTube history, searching on the word "music" but I've listened to too much music. Or maybe YouTube had started sending me random shit to listen to, because some of the things that came up in history I didn't remember and others I can't even imagine myself listening to. What to do?

After a bit I remembered that the guy who did the cover that I was in love with was named George. George who? George B-something. Well it turns out that that's all you need to tell YouTube. Because I type "George b" and it pops up "george barrett get lucky," which is just what I wanted.

After a bit I remembered that the guy who did the cover that I was in love with was named George. George who? George B-something. Well it turns out that that's all you need to tell YouTube. Because I type "George b" and it pops up "george barrett get lucky," which is just what I wanted.<3

What George does is sing lead, harmony and backing vocals. Drum set, bass, lead guitar, electronic keyboard, piano, tambourine, cowbell, and a few other percussion instruments, all stuff I'd like to do. And with passion and energy that I don't think that I can duplicate. But jeez, I'd love to.

And now, for those interested, here's the video:

Feb 14, 2015

Valentine's day book review: "The Martian"

For Valentine's day, Bobbi got me a copy of a book called "The Martian." She didn't buy it for me. She's way too clever for that. She took out of the library. That way I didn't have to figure out what book to throw out to make space for it if I liked it, and she didn't have to regret buying it if I didn't.

Win!

I finished it in one day. Could not get to sleep without reading it to the end.

The book had me at the first line. Here it is:

And the hundredth time is a tie.

Win!

I finished it in one day. Could not get to sleep without reading it to the end.

The book had me at the first line. Here it is:

I'm pretty much fucked*.That may not be your idea of great literature, but if you put "Call me Ishmael," one of the official best opening lines of all time up against "I'm pretty much fucked," "I'm pretty much fucked" wins 99 times out of a hundred.

And the hundredth time is a tie.

How about "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times..."

Nope. "I'm pretty much fucked" wins.

Those are the best opening lines from memory. But you know me (or maybe you don't). Research is my middle name. I looked up "100 Best First Lines from Novels".

I'm not through the whole list, and I gotta say there are some contenders, but "I'm pretty much fucked." is still tops for me.

Some books start out great, and go down from there. And you'd think that with an opening like "I'm pretty much fucked," that you'd have no place to go but down. But no. The rest of the book does not disappoint.

You can get "The Martian" at Amazon. Or you can do what Bobbi did, and get it at the Blue Hill Public Library.

* Wikipedia has a page for fuck. Of course they would.

Feb 12, 2015

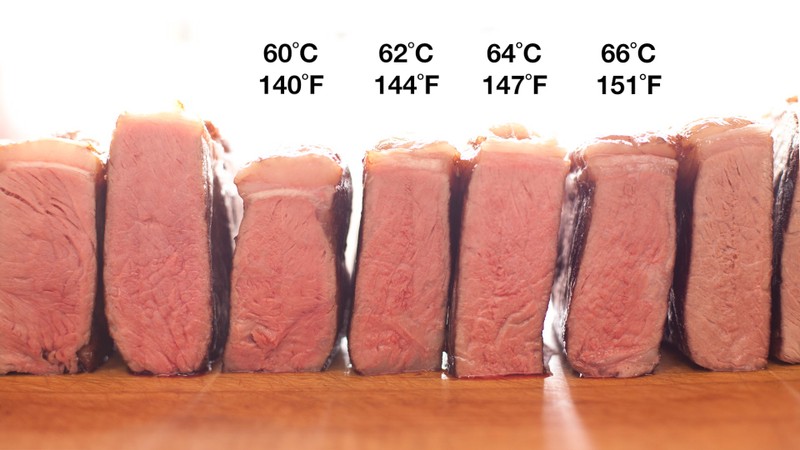

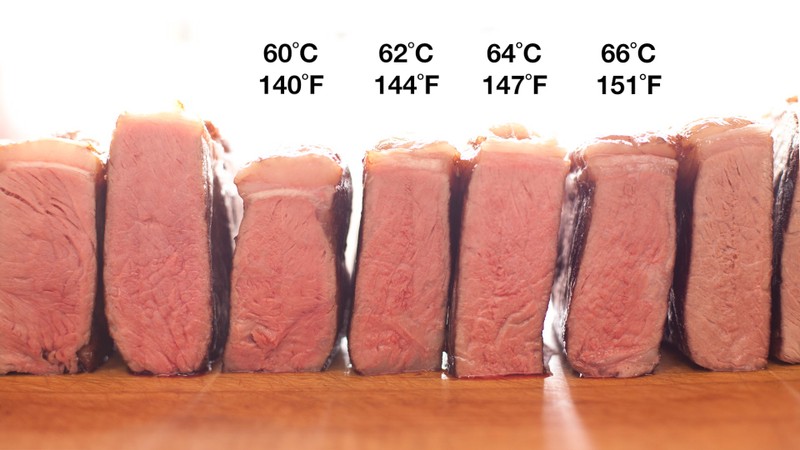

Sous vide, pour moi

I ordered the ANOVA Sous Vide cooker on the date of this post. It arrived a few days later and a few days after that I got Amazon's recommended sous vide container and cover. I chopped a hole in the top with an electric saw (jig, not circular) and mounted the cooker. Then I cooked my first Sous Vide meal: some cheap stack that turned out pretty delicious.

I'd gotten a vacuum sealer, so I put four pieces of steak in vacuum, and cooked them up at 62°C after presearing.

Two went in the freezer, one went in the fridge to be consumed the following night, and one went in my mouth.

Yum.

I used this as my guide.

I also worked out the logistics of cooking sous vide steak for several people.

Once you hit the target temperature the steak does not get weller done; it just gets more tender. So cook the well-done steaks first. Then lower the temperature to medium and cook them (the well-done steaks can stay in the cooker). Then lower to the rare, and the rarest and keep it there until it's time to serve. At serving time you can re-sear the steaks to make them sizzle a bit.

I'd gotten a vacuum sealer, so I put four pieces of steak in vacuum, and cooked them up at 62°C after presearing.

Two went in the freezer, one went in the fridge to be consumed the following night, and one went in my mouth.

Yum.

I used this as my guide.

I also worked out the logistics of cooking sous vide steak for several people.

Once you hit the target temperature the steak does not get weller done; it just gets more tender. So cook the well-done steaks first. Then lower the temperature to medium and cook them (the well-done steaks can stay in the cooker). Then lower to the rare, and the rarest and keep it there until it's time to serve. At serving time you can re-sear the steaks to make them sizzle a bit.

Feb 9, 2015

I love Google: Labeling or labelling, which is it?

In a previous post, I said:

Note: PLP is Post Labeling Paralysis and FLT is Fuck Labeling Paralysis in the United States. In Canada and the rest of the English speaking world PLP is Post Labelling Paralysis, and FLT is Fuck Labelling Therapy, with two l's in case you didn't notice. One more example of American Exceptionalism. Spelling reference here. Ridiculously obsessive follow-up post on spelling, here.

That last 'here' is this post, wherein I present the evidence to back up the assertion, courtesy of Google. Google can grovel over its collection of scanned and otherwise electronified books and tells us the relative use of the alternative spellings.

|

|

So, you see, American books do choose one 'l' by a vast margin, and Brits choose two 'l's, to a smaller, but still very significant degree.

To see and play with the data, click on the image or caption. Trust me, it's cool.

To see and play with the data, click on the image or caption. Trust me, it's cool.

Feb 8, 2015

Post Labelling Paralysis

I've found myself unable to post regularly for all sorts of stupid reasons. One of the stupidest I'll call Post Labeling* Paralysis. In this post, I'll explain the condition, what I did initially to transcend it, and what I'm doing now.

First, the condition. A diagnosis of Post Labeling Paralysis indicated when a one has written a new post, is about to publish it, can't figure out what to label it, and becomes paralyzed. PLP occurs when writers consider labeling a post to be vitally important. If a post is labeled, they reason, it lets readers easily find similar posts to one they found interesting, thus improving their blog-reading experience. Therefore, posts should always be labeled.

PLP's behavioral effects can be mitigated by instructing the PLP-sufferer to say: "Fuck labeling this post. I'm publishing it anyway," and then to hit the Publish button. This is known as Fuck Labeling Therapy, or FLT, and has been shown to be an effective intervention.

After sufficient FLT, a PLP sufferer may enter the post PLP stage, or PPLP. During the PPLP stage one no longer has to apply FLT techniques to publish a post. As one former sufferer says: "You don't think about labeling any more. You just push the fucking button."

Ultimately the PPLP phase may result in a series of Post Labeling Epiphanies (PLEs) during which the proper post label naturally suggests itself and is applied without hesitation. For example, metablogging for this one.

Reversion to PLP, if it does occur, can be handled by further application of FLT.

Note: PLP is Post Labeling Paralysis and FLT is Fuck Labeling Paralysis in the United States only. In Canada and the rest of the English speaking world PLP is Post Labelling Paralysis, and FLT is Fuck Labelling Therapy, with two l's in case you didn't notice. One more example of American Exceptionalism. Spelling reference here. Ridiculously obsessive follow-up post on spelling, here.

First, the condition. A diagnosis of Post Labeling Paralysis indicated when a one has written a new post, is about to publish it, can't figure out what to label it, and becomes paralyzed. PLP occurs when writers consider labeling a post to be vitally important. If a post is labeled, they reason, it lets readers easily find similar posts to one they found interesting, thus improving their blog-reading experience. Therefore, posts should always be labeled.

PLP's behavioral effects can be mitigated by instructing the PLP-sufferer to say: "Fuck labeling this post. I'm publishing it anyway," and then to hit the Publish button. This is known as Fuck Labeling Therapy, or FLT, and has been shown to be an effective intervention.

After sufficient FLT, a PLP sufferer may enter the post PLP stage, or PPLP. During the PPLP stage one no longer has to apply FLT techniques to publish a post. As one former sufferer says: "You don't think about labeling any more. You just push the fucking button."

Ultimately the PPLP phase may result in a series of Post Labeling Epiphanies (PLEs) during which the proper post label naturally suggests itself and is applied without hesitation. For example, metablogging for this one.

Reversion to PLP, if it does occur, can be handled by further application of FLT.

Note: PLP is Post Labeling Paralysis and FLT is Fuck Labeling Paralysis in the United States only. In Canada and the rest of the English speaking world PLP is Post Labelling Paralysis, and FLT is Fuck Labelling Therapy, with two l's in case you didn't notice. One more example of American Exceptionalism. Spelling reference here. Ridiculously obsessive follow-up post on spelling, here.

Feb 7, 2015

Interesting stuff on the Internet (Part N)

Open Culture is a site that says that it

... brings together high-quality cultural & educational media for the worldwide lifelong learning community. Web 2.0 has given us great amounts of intelligent audio and video. It’s all free. It’s all enriching. But it’s also scattered across the web, and not easy to find. Our whole mission is to centralize this content, curate it, and give you access to this high quality content whenever and wherever you want it. Some of our major resource collections include:

- 950 Free Online Courses from Top Universities

- 675 Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, etc.

- 550 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free

- 600 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

- MOOCs from Great Universities (Many With Certificates)

- Learn 46 Languages Online for Free: Spanish, Chinese, English & More

- 200 Free Kids Educational Resources: Video Lessons, Apps, Books, Websites & More

Well, there's even more. I followed the link to one of the movies and found the Internet Archive's collection of movies, here. Thousands of them! And that is only a part of what the Internet Archive is archiving. Apart from the somewhat well-known "Wayback Machine," which archives and lets you search web pages that have been since removed, the Internet archive has audio, video, and a library with a million volumes.

It's not just old crap that nobody wants. I'm reading Steven Pinker's "The Sense of Style" and wanted to see which of his books are in the lending library. The answer is lots. You have to be a member of a participating library, but if you are then there are about 100,000 fairly recent eBooks available. The Blue Hill library is not a member, but the Bangor Library, for which I have a card, is.

Find out if your library is a member, here.

Feb 6, 2015

Google Flight Search (Part of the I Love Google Series)

Here's another bit of googly wonderfulness that I just discovered: Google Flight Search.

Here's the deal: you want to fly from here to there, where "here" might include a bunch of nearby and not-quite-so-nearby airports, and "there" is somewhere else. And you want to take the flight that's going to be least expensive.

Now there are tradeoffs, of course. You might be willing to go to a different city than your destination city, if the price was right. Or you might be willing to shift backward or forward a day, or even a week, depending on the price.

You might also be willing to extend your trip by a few days, or shorten it by a few days. You're interested in a lot of information, pulled from diverse sources, and pulled together in a consumable way. And you'd like to be able to ask for what you want efficiently and not have to do what I used to do: make 20 different queries and remember which query produced what results.

Google Flight Search lets you do all that. Here's how.

Start at: https://www.google.com/flights/ or https://flights.google.com, which takes you to the same place.

Now enter your departure and destination cities. I enter Bangor, or airport code BGR, and my destination, San Francisco (SFO). Flight search gives me a list of outbound flights, and a tip (just below the blue box with the arrow.) I can save $88 if I leave from Portland.

Sweet!

So I click the + sign next to Bangor and the drop-down lets me add Portland (and reminds me of the saving).

Nothing particularly looks better, so I look at the map view to see if there's anything to be found there.

The map shows me the best price if I fly into a different city. For this flight there's nothing better. And $425 is pretty good for a coast-to-coast round trip flight.

But if was crazy mad for savings, I could look at the some other departure airports and discover that I could do the trip for $403 from Manchester, NH, or $405 for Boston.

Awesome!

Here's the deal: you want to fly from here to there, where "here" might include a bunch of nearby and not-quite-so-nearby airports, and "there" is somewhere else. And you want to take the flight that's going to be least expensive.

Now there are tradeoffs, of course. You might be willing to go to a different city than your destination city, if the price was right. Or you might be willing to shift backward or forward a day, or even a week, depending on the price.

You might also be willing to extend your trip by a few days, or shorten it by a few days. You're interested in a lot of information, pulled from diverse sources, and pulled together in a consumable way. And you'd like to be able to ask for what you want efficiently and not have to do what I used to do: make 20 different queries and remember which query produced what results.

Google Flight Search lets you do all that. Here's how.

Start at: https://www.google.com/flights/ or https://flights.google.com, which takes you to the same place.

Now enter your departure and destination cities. I enter Bangor, or airport code BGR, and my destination, San Francisco (SFO). Flight search gives me a list of outbound flights, and a tip (just below the blue box with the arrow.) I can save $88 if I leave from Portland.

Sweet!

So I click the + sign next to Bangor and the drop-down lets me add Portland (and reminds me of the saving).

And it gives me another tip. I can save a few more bucks if I change my departure. Sweeter!

If I want to, I can look at other possible departure days:

Nothing particularly looks better, so I look at the map view to see if there's anything to be found there.

The map shows me the best price if I fly into a different city. For this flight there's nothing better. And $425 is pretty good for a coast-to-coast round trip flight.

But if was crazy mad for savings, I could look at the some other departure airports and discover that I could do the trip for $403 from Manchester, NH, or $405 for Boston.

Awesome!

Feb 5, 2015

People I want to be when I grow up: Scott Alexander

| Yvain rescues the lion. Medieval illumination (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

"Scott Alexander" is not his real name. As he says on his about page:

I am going by Scott S Alexander, which is almost but not quite my real name. If you know my real name, please don’t use it on here.I know his real name. And I'm not going to use it. But if you care, you can find more about him here, where he explains the problems he's had using his real name:

After years of trying the opposite policy, I’m switching to acting all clever and not having every detail of my life accessible to anyone who tries to search for me on the Internet. Somebody who doesn't like me - I am not sure who, but I work in mental health and guess this is sort of a professional hazard - has been trying to systematically discredit me by posting racist and profanity-laden things under my name. Some of the comments make some effort to convince, like linking back to my website.I'm not sure when I first came across "Scott". It might have been on LessWrong where he blogs under the handle Yvain. Or on http://raikoth.net, where he's posted some long essays, my favorite of which is The Non-Libertarian FAQ (aka Why I Hate Your Freedom) a 30,000 word, well-reasoned critique of libertarianism that I really, really, really wish I had written. Or even thought of.

Almost everything he writes is painstakingly researched and engagingly written. If you'd like to sample the best of his writing he's got a page on Slate Star Codex called "Top Posts." Makes me want to go and reread the ones that I remember, and read the ones that I don't know to see what I've missed.

Which I just did for about half an hour.

Crap!

Feb 4, 2015

Under Milk Wood

Years ago, I saw a performance of Dylan Thomas' "Under Milk Wood" on TV. I fell in love with it. At the end of this post I've embedded a YouTube recording of Richard Burton reading it and find out for yourself how wonderful it sounds.

Every once in a while I get ambitious and decide I'm going to memorize it. I've not gotten very far. I learn a bit, then abandon the project. Sometimes I relearn what I had once learned. Sometimes I go a bit further. There's a high likelihood that I'll die before I learn the whole thing. Still it's something to aspire to.

Every once in a while I get ambitious and decide I'm going to memorize it. I've not gotten very far. I learn a bit, then abandon the project. Sometimes I relearn what I had once learned. Sometimes I go a bit further. There's a high likelihood that I'll die before I learn the whole thing. Still it's something to aspire to.

I've been thinking a lot about memory, both what's there and what's gone missing, and I'm thinking about recovering my earlier knowledge and learning a bit more. So, by way of starting the process here is what I remember, right now (this is not authoritative. There are a couple of errors. For the real thing, I've provided a link.

Nonetheless, from memory:

To begin, at the beginning.

It is spring, moonless night in the small town, starless, and bible-black, the cobble streets silent, and the hunched, courters' and rabbits' wood limping invisible down to the slow black, sloe black, crow black fishing boat bobbing sea.

The houses are blind as moles (though moles see fine tonight in the snouting, velvet dingles) or blind as Captain Cat, there in the muffled middle by the pump and the town clock, the shops in mourning, the welfare hall in widow's weeds. And all the people in the lulled and dumbfound town are sleeping.

Hush! The babies are sleeping. The farmers, the fishers, the tradesmen and pensioners. Cobbler, schoolteacher, postman and publican, the undertaker and the fancy woman. Drunkard, dressmaker, preacher policeman, the webfoot cockle-woman and the tidy wives.

Young girls lie bedded soft, or glide in their dreams with rings and trousseaux, bridesmaided by glowworms down the aisle of the organ-playing wood. The boys are dreaming wicked, or of the bucking ranches of the night and the jolly-rogered sea. And the anthracite statues of the horses sleep in the fields, and the cows in the byres, and the dogs in the wet-nosed yards. And the cats lope sly, streaking and needling, on the one cloud of the roofs.

You can hear the dew fall and the hushed town breathing.

And you alone can see [hear] the invisible starfall, the darkest-before-dawn minutely dew-grazed stir of the black, dab-filled sea where [A bunch of boats, which may include, but not necessarily in this order] the Arethusa, the Skylark, Zanzibar, Rhianon, the Cormorant and the Star of Wales tilt, and ride.

You can hear the dew fall, and the hushed town breathing.

And so on.

Here is the text. And here is a fabulous reading of this same part (and more) by Richard Burton, with the first part embedded in the post:

Feb 3, 2015

I'm Star Stuff

Today I'll tell you what I am: I'm star stuff.

It's actually a pretty cool thing to meditate on. I can sit here, close my eyes, put my attention out in all directions, back in time, to the start of time, and know that where I am is where it all started; the center of the earth. The location of the Big Bang.

And I can think about the history of the universe as we know it that led to my arriving at this precise spot at this precise time. Think about how the atoms that make up my body, apart from the Hydrogen ones, were made in stars; my body is the built from the corpses of many, many stars.

Here's how it all came about.

If God said "Let there be light!" the universe didn't hop right to it. According to our best models, It took a full ten seconds for things after the Big Bang for the universe to cool enough for photons to appear. That was the start of the Photon Epoch. Even though there were lots of photons there wasn't what you'd call light. For one thing the photons kept bumping into stuff. It was about 380,000 years before the universe started to become transparent enough for photons to travel any distance.

But even though there were photons, the universe was still a pretty dark place. There were no concentrated sources of photons beaming out. No stars. Near perfect blackness. What you see between the stars today, only more so.

Stars didn't appear until around 400 million years after the Big Bang. Finally there was light. But those early stars were very different from most of the stars we can see today. Scientists divide stars into three populations: ones like our sun are Population 1 stars. They are relatively young and fairly hot. In other parts of the universe are Population 2 stars. They are generally much older and almost always much cooler. The very oldest stars are population 3 stars. They are the ancestors of all population 1 and 2 stars. The difference between Population 1, 2 and 3 stars is explained by metalicity--the proportion of matter other than Hydrogen and Helium in s star.

When the first stars were formed, the universe was made almost entirely out of hydrogen (92% by number of atoms, 75% by mass) and Helium (8% by number of atoms, 25% by mass) along with really tiny trace amounts of very light nuclei, up through lithium. There was no oxygen, so no water; no carbon, so no carbohydrates; no nitrogen, so not proteins; no calcium, nitrogen, sodium, so no possibility of me.

To the extent that I could be said to exist at all, I was just gas. Eventually some of the hydrogen and helium in the universe came together--dark matter is implicated in the process--and after that happened gravitational forces pulled more and more Hydrogen and Helium into the growing mass until, at some point--there's debate on exactly when and how--the object became dense enough and hot enough to trigger a nuclear reaction, like the one that lights our sun and the other stars that we see.

Those nuclear reactions produce all the heavier elements. Some, are produced the normal course of a star's lifetime, but most are produced when stars explode, go nova. Eventually some of the Hydrogen, Helium, and--importantly--the other elements form new stars, and some of them go through the same process, producing even more of the heavy elements.

The first stars, called Population 3 stars had no heavy elements--because there were none. The second kind of stars have few heavy elements. They are mostly older stars and formed before metals were abundant. As more and more stars produced more and more heavy elements the composition of the universe changed.

So I'm the result of exploding Population 3 and Population 2 and maybe some Population 1 stars.

Cool!

Feb 2, 2015

I'm Mike, From Right Here, The Center of the Universe

| Galaxies are so large that stars can be considered particles next to them (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In the first meeting, I introduced myself, saying: "I'm Mike Wolf, from planet Earth."

I don't usually introduce myself that way. Oddly, I learned that one of the other people in the group regularly introduces himself that way (the "from planet Earth" part, not the "I'm Mike Wolf" part.)

Later, I explained: "I'm not a native. I'm visiting." But that's not quite right, so I thought I'd start by correcting the record.

I'm a science guy. I majored in math and minored in physics at MIT and according to the best science we know, I am, right here and right now, at the exact center of the universe. I find it helpful to remind myself of that, every once in a while. So I'm from here, the exact center of the universe.

Here's why the available evidence points to that.

According to modern science, the origin story of the universe--and thus of each of us--is some variation of what's called the "Big Bang Theory." According to the theory, the universe has not been around forever. We believe that started about 13.798 ± 0.037 billion years ago from a single point, and it's been expanding ever since. There's quite a bit of speculation about what happened during the first trillionth of a second, but after about 10−11 seconds, things are fairly well understood.

Two things we know with high certainty and have known for a long time: the speed of light in a vacuum is constant, and the universe is expanding. We also know that the further away an object it, the faster it's travelling away from us.

So we know that when we look further and further out in space we are actually looking further and further back in time. At cosmological scales the standard unit of distance measurement is a light-year, which is the distance that light travels in one year. What that means is that any light we see from an object a light-year away was really produced a year ago.

Two things we know with high certainty and have known for a long time: the speed of light in a vacuum is constant, and the universe is expanding. We also know that the further away an object it, the faster it's travelling away from us.

So we know that when we look further and further out in space we are actually looking further and further back in time. At cosmological scales the standard unit of distance measurement is a light-year, which is the distance that light travels in one year. What that means is that any light we see from an object a light-year away was really produced a year ago.

The oldest and most distant galaxy we've seen so far is 13.1 billion light-years away, which means that the light from that galaxy was emanated 13.1 billion years ago, or a mere 700 million years after the universe started. But that's not the most ancient electromagnetic emanation that we've detected. It turns out that there's something called the Cosmic Microwave Background, only detectable with radio telescopes, which is believed to be the afterglow of the Big Bang itself.

Now think about where that Big Bang happened. Let's suppose it happened a billion miles in that direction. If it did then when we aimed our radio telescopes in that direction we'd see a stronger glow than if we aimed our radio telescopes in some other direction. But that's not what we see. What we see is that the glow is uniform in every direction which means, that no matter where you are, you are at the place where the big bang happened.

So this spot, right here, if you went back in time, would be the center of the universe. I am at the center of the universe. But the really cool thing is that each of you are at the center, too. We are all, each at the place where, long, long ago, the universe began.

Feb 1, 2015

Tasteless humor

|

| No political correctness (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

Anyway I've now given you a whole paragraph in which to decide whether you want to read a joke that I guarantee is tasteless and I believe (but do not guarantee) is funny. Oh, what the hell. I guarantee it's funny, too. Or double your money back.

This was prompted by one of my daughters sending me a link to this article: "Singing show tunes helps fight off dementia: study."

|

| English: Early 1990s TaB Clear soda can (US, 12 oz.--355 ml.) (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

Philip was frustrated. It didn't as all go as he'd planned. He tried to get them to learn the music--and they did--sort of. But some would sing the first measure while other sang the second and others the fifth. Same thing with the words. They'd learn the words--some of them--and then they'd add their own words and they'd sing them in whatever order pleased them. Same with the tempo.

It was chaos. And not musical at all.

But he did notice something: when he waved his arms in time with the music, some of the singers matched the tempo. Wrong words, wrong notes, but some had the right tempo. That was an improvement.

One day he picked up the first thing he saw in front of him: a big red apple that he'd packed as part of his lunch and started waving it in one of his hands. One by one the singers locked their eyes on the big, red apple and as they did their singing changed: they started to hit the right notes along with the right words and at the right tempo.

Heartened, he reached down and picked up another bit of his lunch: it happened to be a bright pink can of Tab soda. In his right hand he waved the apple. In his left the soda. And the music changed. It sent chills down his spine. Suddenly the singers were finding the tempo, the notes, and the right words. Once they locked in on them they locked in, solid. And somehow they were singing harmonies--harmonies that he hadn't taught them!

As he continued waving his arms they kept getting better. Their confidence grew, and so did his. They followed every movement of his hands with their voices. Louder, softer, faster, slower. They saw what he wanted and they delivered it.

The connection he'd hoped for was happening. The music was transforming them, and they were transforming the music. Hour by hour they got better and better.

Eventually they were so good that Philip had them perform locally. They astounded everyone who heard them--including a man who was an agent for a recording company. He signed them to a contract. They recorded their music and it went right to the top of the charts.

Within a year they were touring the world led by Phillip, still waving his arms with the two things he'd originally picked up that day. He'd tried different things, but none of them worked. Only a bright red apple and a bright pink can of Tab did the trick.

The singers became famous.

Perhaps you've heard of them.

The Moron Tab and Apple Choir.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)